Feature Well / Summer 2023 Issue

Ohio Poet Laureate Kari Gunter-Seymour uplifts Appalachian artists

Gunter-Seymour, a resident of Athens County, supports local poetry by coordinating readings and helping artists get their work published.

This past February, six students from Southeast Ohio displayed their public speaking skills at Stuart’s Opera House during the Poetry Out Loud Regional Semifinals. The competition challenged the students to perform two rounds of poem readings on stage, with their performance then evaluated by a group of judges.

The students’ readings, powerful in their own distinct ways, show that the heart of poetry is still beating in Southeast Ohio.

Connecting through Poetry

Kari Gunter-Seymour has seen firsthand how poetry enriches Southeast Ohio. Gunter-Seymour is the third and current Poet Laureate of Ohio, selected in 2020 by Ohio Governor Mike DeWine. Now serving her second term, she has only one year left in this position. Still, she has plenty of responsibilities, and her goals remain ambitious.

Even as new events and trips are packed into her already busy schedule, she continues to enjoy her time as poet laureate, making the most out of the opportunity. She lights up when she recalls the people she has worked with so far whether it is a seasoned poet or a group of young students who are just getting their first taste of art.

A large part of her philosophy is driven by her enthusiasm to empower those who have not been properly taught about art and its value.

In January, Gunter-Seymour led virtual workshops with 18 prisons across Ohio in which inmates produced work based on writing prompts. Taking significant pauses in between each word, she describes the results: “So moving, gut-wrenching, gorgeous.”

These are people who have been told that they are unworthy or unfit, Gunter-Seymour says. The same titles burden the women in recovery that she works with. These women often come from abusive relationships and have never been told they deserve better, she explains.

“And I always start things out by sharing that, ‘Hey, I know about labels,’” she says. “I’ve grown up with labels: hillbilly, hick, white trash. I know about labels. I know what it feels like to be less than.”

A Past to Be Proud Of

As a ninth-generation Appalachian woman, Gunter-Seymour has endured negative stereotypes. Still, her lineage remains a source of pride.

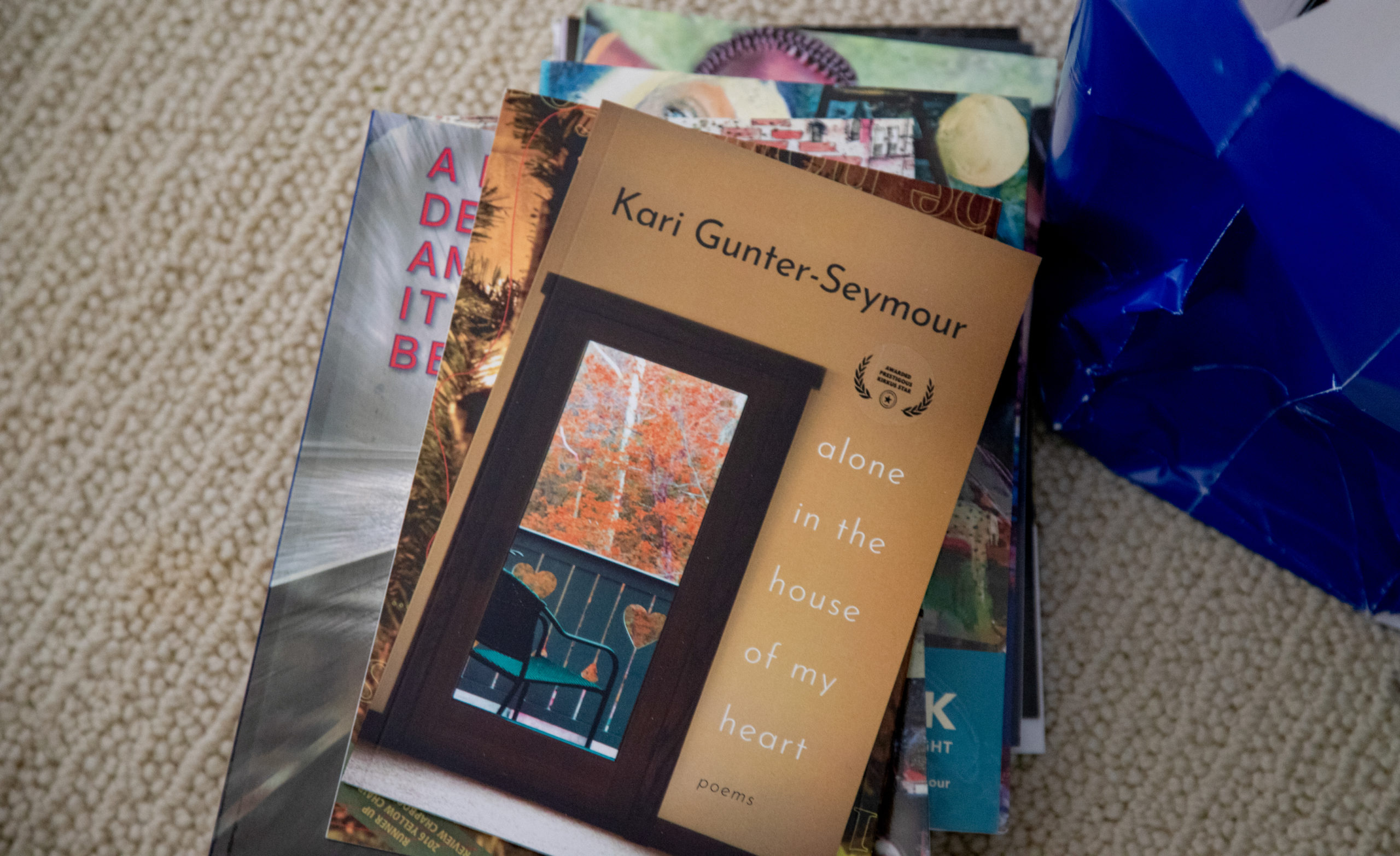

Appalachian identity is the heart and soul of “I Thought I Heard a Cardinal Sing,” a recently published anthology edited by Gunter-Seymour. Released in 2022, it features 134 poets with strong connections to Appalachia.

Grouped together with a hefty stack of other books Gunter-Seymour has published, this anthology resonates with her own history.

Her voice teems with admiration as she narrates the history of her family: a long line of coal-miners turned tobacco farmers. Even the most specific quirks of her ancestors are fresh in her mind. She recounts a great-great-great-great grandmother whose boots were “big and rough” and who looked wild enough to “tackle a den of wildcats.”

Gunter-Seymour speaks of her career as a gift she attributes to her family, but her journey to embracing poetry wasn’t a straight shot. She had an affinity for the arts starting at an early age, writing stories but never sharing them with a wide-ranging audience.

Gunter-Seymour married a coal miner and moved to Meigs County after graduating high school. When the marriage didn’t work out, she decided to go back to school at Ohio University while caring for her three-year-old son.

She wove four or five baskets a day just to feed herself and her son while simultaneously studying counseling. With support from OHIO art professor Bob Borchard, though, she switched her studies to graphic design.

This set her on a path to receive a master’s degree in commercial photography. At the time, Gunter-Seymour relied on journaling to work through the rough patches and was soon told poetry would be a good pursuit for her.

“One woman very kindly told me, ‘Your poetry is not very good. Maybe you should think about doing something else.’ And I said, ‘Hold my beer, because I’m going to do this!” – Kari Gunter-Seymour

“This is it,” she says. “This is what I’ve been looking for my whole life, is this. Those early poems were horrible, but people cared enough to lovingly accept them and listen to me read them.”

Inspired by Life

Gunter-Seymour sees poetry as a way to atone for past mistakes or recognize the wrongdoings perpetrated against marginalized groups. She wonders out loud, audibly perturbed, whether her family had once owned slaves.

“So then, I need to admit that and I need to make compensation for that by my actions and what I choose to do and how I choose to talk about it and how I choose to stand up for it,” Gunter-Seymour says.

When it comes to the writing process, Gunter-Seymour turns to a few methods to manifest her thoughts into words. At times, she might find inspiration in a pile of paper scraps. When she really cannot think of anything, she looks at the world around her.

To show what she means, Gunter-Seymour plucks a small shell with a spiral pattern from a bowl and rattles off a list of adjectives and nouns: ridges, rust-color, gray, circular, infinity, pockmarked.

“All of a sudden, you’ve got a jumping off point and you’ve got a poem in there somewhere, or story or song,” she says. “I encourage everybody to do that kind of thing.”

One of the more meaningful places in Gunter-Seymour’s life, potentially the most abundant source of inspiration, lies right in her own backyard.

A steep gravel path descends into a valley that is filled with traces of fond memories. Once Gunter-Seymour is there, she is surrounded by sprawling hills where trails snake around the entire property. Her house sits atop the highest point like a crown.

Come summertime, Gunter-Seymour and her family spend entire days here together. During quieter seasons when she strolls through this sanctuary alone, she can’t help but think of a new poem. She describes this as her happy place, where her poetry imitates life.

Bringing Poets Together

As Poet Laureate of Ohio, a top priority for Gunter-Seymour is to uplift aspiring poets all across the state.

“That’s really a wonderful part of this, is being able to promote people in that way and help them get a leg up,” she says.

Athens Poet Laureate Stephanie Kendrick believes Gunter-Seymour is a pioneer in Athens County, opening doors for writers and guiding them to the right platforms.

Kendrick met Gunter-Seymour through the Women of Appalachia Project and eventually worked with her to create a space for residents of Athens to feel comfortable sharing poetry.

After their plans to start open mic nights were scrapped due to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the two realized that it could be done online. This marked the start of the Athens County Poets and Storytellers Group.

There were even several poets who joined internationally, including regulars from New Zealand and Trinidad. Though the group stopped its virtual open mic nights in 2022, its Facebook page is still open as a hub for members to connect. A lot of close relationships were built there and remain to this day, Kendrick says.

“Those connections – pulling people into Athens and helping them experience our region –have translated from virtual to in-person, which has been pretty neat to see,” Kendrick says.

A Lasting Desire to Serve

Gunter-Seymour knows poetry might not be for everyone, but she still encourages people to read one or two poems a day or try out a workshop. She hopes they can see the true value of poetry and other art forms.

“The true story is in the painting or in the literature of the time,” Gunter-Seymour says. “The history book will gloss over something or leave something completely out, but the artists do not.”

Gunter-Seymour stands near her empty garden, contemplating her future as a cool wind picks up. She isn’t quite sure what she’ll do after her laureateship ends in December.

“Do people still call on you if you’re not the poet laureate?” she asks herself aloud. “I don’t know. I don’t know the answer to that.”

Gunter-Seymour knows she will keep writing and hopes to meet with her workshop group forever. She aspires to keep connecting with the students, inmates and women in recovery whose stories have continued to motivate her.

“I’m Appalachian,” she says. “It’s about giving back, it’s about service, it’s about community and belonging.”

SEO

Related posts

What’s Inside

- Behind the Bite (68)

- Features (124)

- In Your Neighborhood (102)

- Photo Essay (4)

- Read the Full Issue (8)

- Talking Points (48)

- The Scene (15)

- Uncategorized (3)

- Web Exclusive (5)

- What's Your Story? (21)

Find us on Social Media