Nelsonville Food Cupboard, powered by volunteers, feeds the hungry and fosters community

On a cold Saturday in February, the sidewalk outside the Nelsonville Food Cupboard is covered in a thick slab of ice. On another day of the week, it might not be a problem. But Saturday is a distribution day, and from noon to three a steady stream of volunteers are tasked with lugging boxes filled with food across the icy thoroughfare.

But Capi Huffman isn’t fazed. She conducts the pantry’s activities on Saturdays, and she wastes no time pulling her jacket up over her face mask, grabbing a snow shovel and stepping out into the winter sun. Cracks and crunches pierce the air, as she begins to chip away at the ice. There are easier jobs to do, especially on a day so cold, but before long the slippery sheet is reduced to hundreds of harmless chips.

But there is another problem waiting for her when she returns inside. A black sedan had just pulled up, and the driver requested food. Chelsea Dunfee-Rivas, sitting at a small wooden desk in the corner and typing furiously on her laptop keyboard, is attending to the issue. Anytime someone drives up and requests a box of food, she enters their information into PantryTrak, a program designed to link food pantries across the country so they can share data.

When Dunfee-Rivas sees that the man is from Logan, she calls Huffman over. For a minute or two, they deliberate in whispers. The cupboard is only supposed to supply it to people from Athens County.

The man from Logan is waiting in his car, and, whether he knows it or not, his dinner might be hanging in the balance.

Huffman sighs and adjusts her mask.

“Let’s give it to him. I’m sure he needs it,” Huffman says.

In a day’s work

The main room of the food cupboard is dimly lit and separated by a shoulder-high wall that splits the room into front and back sections. In the back, the boxes of food are assembled. In the front, they are stacked full of more food and shuttled to cars where hungry drivers and their families await much-needed ingredients, snacks and pre-made meals.

The whole place is a hive of activity, with volunteers moving briskly in and out of back rooms and emerging with sleeves of crackers, frozen chicken and cartons of eggs. Christy Meyers is one of those volunteers, and her laugh is so authentic and so frequent that it might as well be the cupboard’s in-house soundtrack. She peeks at her phone to check the time. Her German Shepard is home alone, and its bladder isn’t exactly trustworthy. She passes through a doorway with a cardboard box lifted near her head.

At the same time, Lora Blankenship dips under her, carrying a birthday cake from the storage area into the main room. Someone outside had asked if they had one, and Blankenship was determined to deliver. Coronavirus or not, employed or unemployed, every parent wants their child to have a birthday cake.

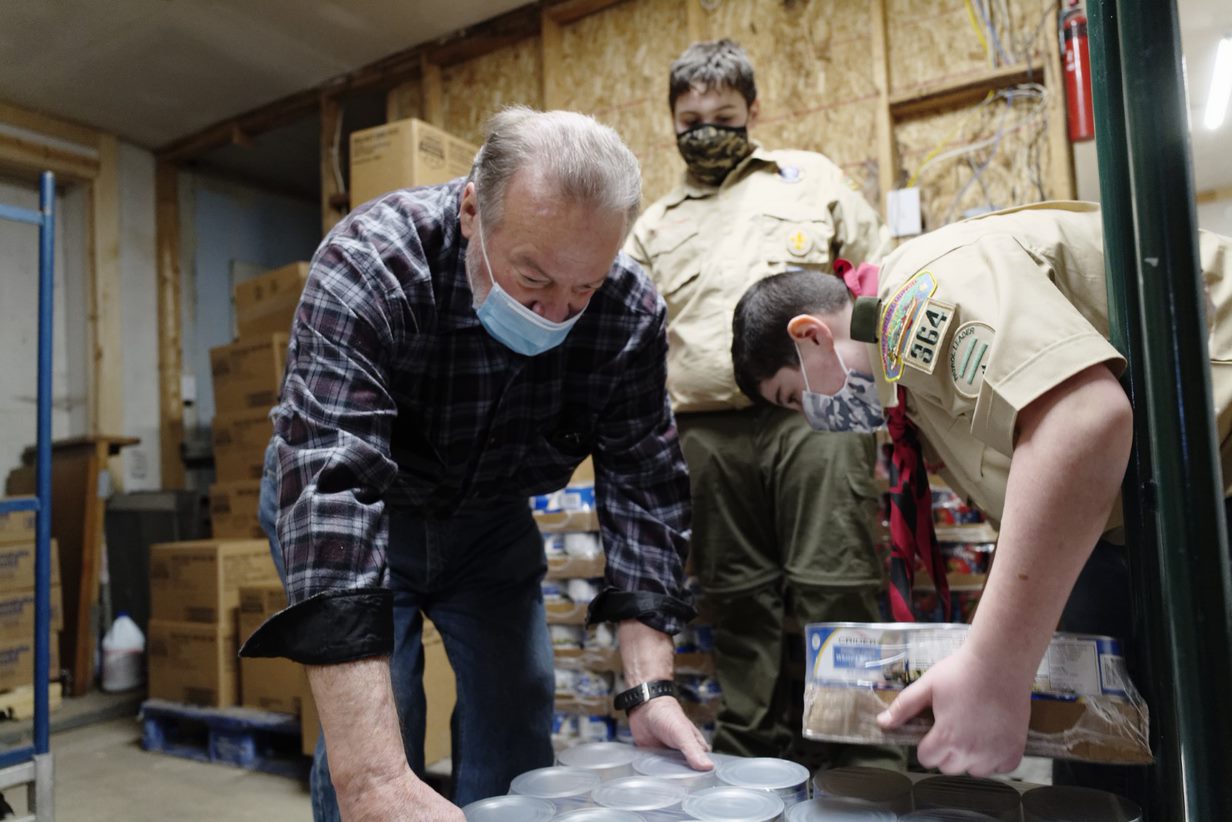

In the back, on the other side of the wall, a gray-haired volunteer named Bruce Keeney is commanding a small unit of three Boy Scouts from Troop 364. As Keeney looks on and paces around a massive table, the boys toss cans of beans into cardboard boxes. But when his attention is diverted, the boys breathe deeply and act once again like middle schoolers; elbowing and razzing each other while suppressing some bathroom-joke-induced laughter.

They are hard workers, though. Keeney makes sure their service hours are not wasted, and by the end of the day the three scouts are humming along with speed and efficiency. Three hours ago they were khaki-clad boys covered in service patches. Now, they’re a team.

A doorway in the big room opens up into a room of equal size on the other side of the wall. Most of the non-perishable food is stored there. On a good day, the room is stocked full. Saturday, luckily, is one of those days.

Larry and Pat Riley picked up expired and nearly-expired food from Walmart and Kroger earlier in the week to ensure that the cupboard’s supply could meet the demand. Most of the food comes from those two places, but some of it is donated by members of the community.

It’s in this room where Blankenship is busy sifting through a box filled with animal crackers and mini-donuts.

The topic turns to the poverty crisis in Los Angeles, and how the high cost of living, in conjunction with the coronavirus, has forced some Californians into homelessness.

Her response is immediate, almost reflexive.

“Well, a lot of people can’t afford to live here either,” Blankenship says.

Someone mentions the communities of homeless people that have grown under LA’s highway overpasses. Her head drops.

“Is that right? Here they all live in the woods.”

Icicles are hanging from the trees outside. And there isn’t a hint of exaggeration in her eyes.

High on Help, Low on Funds

The impassioned speech that Cincinnati Bengals quarterback, and Athens High School alumnus, Joe Burrow gave when he accepted the Heisman Trophy in 2019 led to more than half a million dollars in donations for the Athens County Food Pantry. With that money, the food pantry was able to expand its operation and buy a truck to move and deliver food.

But pantries like the Nelsonville Food Cupboard, only minutes away, have seen no such influx. Without a gridiron savior to give it a national shoutout, it’s still largely reliant on a small network of devoted volunteers.

“I know they [people in Athens] have it hard, but there are people here who need a lot of help,” Blankenship says.

In that moment, the ice outside of the Nelsonville Food Cupboard isn’t an immediate concern, but another storm could change all that. For many in Nelsonville, just like in the rest of the region, the patches of ice are everywhere, and getting back up is not always guaranteed.

But rain or shine, the cupboard will still be there for those who need it, offering them not just food, but the support of its most compassionate neighbors.

Related posts

What’s Inside

- Behind the Bite (68)

- Features (124)

- In Your Neighborhood (102)

- Photo Essay (4)

- Read the Full Issue (8)

- Talking Points (48)

- The Scene (15)

- Uncategorized (3)

- Web Exclusive (5)

- What's Your Story? (21)

Find us on Social Media