GALLIPOLIS — A gazebo sits in the middle of the town square that overlooks the Ohio River. Teenagers mill about, laughing and watching passersby. Families sit on benches and children climb the oak trees that jut up around the square. A jogger with his dog amble past a memorial dedicated to veterans, and drivers make their way through the main street in town, passing the post office, an insurance company and a three-story brick building that presides over the rest.

This stately structure, The Ariel-Ann Carson Dater Performing Arts Centre, acts as a community hub, hosting The Ohio Valley Symphony’s performances, student music lessons, concerts, events and lectures.

The three-story brick complex juts out over the jewelry store and The Colony Club restaurant next door. Red awnings don the first floor windows and a large red-lit sign of an A draws the eye to an otherwise monotone building. Its outside maintains an industrial, more modern ambience with its simple brick pattern and large windows.

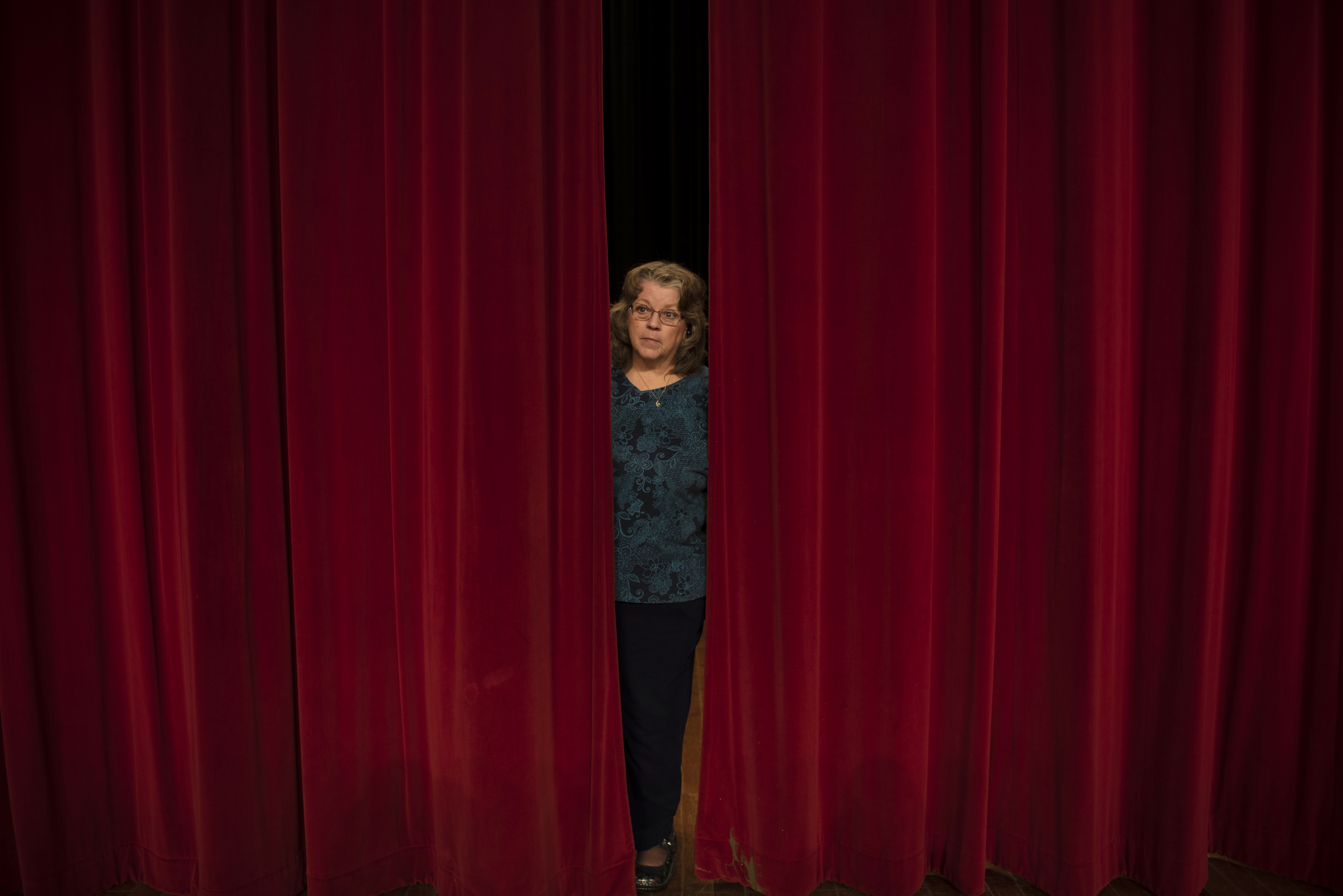

But inside, it exudes the regal splendor of the nineteenth century — thanks in large part to one woman’s ambitions and her community’s help.

Recreating History

Lora Lynn Snow had always wanted to start her own orchestra. The youngest of a large family from Charleston, West Virginia, Snow played with hand-me-down instruments and never received formal music lessons. She loved to watch different musical variety shows on TV like Donny & Marie and Sonny & Cher. When she was in junior high, she heard a pop song on the radio that featured an oboe and decided she wanted to play the instrument. Her love for music only flourished since. Snow has performed with many different symphonies and taught music to students at every level, from kindergarteners to graduate students. But the idea of starting her own orchestra remained unfulfilled — until 1987.

She heard about a building built in 1895 with a theater that had been abandoned for 25 years on Second Avenue in Gallipolis. The Ariel Odd Fellows had built and used it as a lodge for several years before it changed hands to the Gallia Masonic Co. in 1918. Snow says she knew immediately that this would be the home for her future symphony.

When Snow first stepped inside the old opera house, the doors to the theater were chained shut, and the doors were painted an “ugly green.” Cobwebs hung on the rafters, and the stage was covered in hemp ropes and so much pigeon excrement that she called the CDC and brought in three respirators. She hired three stage hands to help clear the stage and hosted a clean-up party a few days later. She and her husband stayed up all that night and filled up a truck with trash. When the public came to help two days later, they filled up another two trucks.

That was just the beginning of the public’s help. When Snow needed to remove much of the old duct work, a family offered to help and then recycled the metal for money.

“They’re helping us out, we’re helping them,” Snow says. “That was just one of many times where we built this two-way street. There should always be something back and forth. I feel very strongly about that. Whatever deal that is going on, however small or large, it needs to be beneficial both ways, or three ways or four ways.”

On April 1,1989, Snow held the first performance of The Ohio Valley Symphony in the half-finished theater. The building had no running water, no heat and no chairs. The outside temperature was 30 degrees the night before, so the audience dressed in winter coats while the orchestra practiced scales to warm up. Although the audience kept slipping forward in the folding chairs borrowed from local funeral homes, the inconveniences were worth it.

“The whole floor was packed, and it was magic,” Snow says. “You get a handful of times in your life where you’re making magic. And that was one of them. Everybody went nuts. And you can’t plan those.”

After the first show, offers to help and to make donations came through. Snow began to see her dream come to fruition. They set a grand opening date for June 9, 1990 — more than a year later.

Because she wanted to operate the orchestra as a nonprofit organization, Snow found she needed to cut corners and find help wherever she could get. When she purchased seats for the theater, she saved money asking people at a local weight lifting clinic to come unpack the trunk, telling them that they wouldn’t have to pay to lift. They came and unloaded the semi-truck full of seats. She also invited a local Cub Scout troop to help gather and recycle the packaging materials.

A beautiful surprise

It was in 1989 that Snow climbed up the scaffolding by herself to start work on the ceiling, thinking that she could not ask people to help her if she couldn’t do it herself. She knocked off a piece of plaster, and that’s when she noticed an ornamental chain design from the 1800s.

The opera house’s history began to unravel with every new discovery.

Hidden away on the side of the stage and up winding stairs were old fragments of carpet and an old cartoonish poster. Snow contacted the League of Historical American Theaters, and they pieced the pattern together and recreated it on a computer. It wouldn’t be until 2018 that they would finally be able to find someone to remake the carpet and have it installed.

The old opera house had been a hub for community events since the mid-1890s. Artists like Will Rogers, Daniel Emmett and the Ziegfeld Follies all performed on its stage. Originally built by the Ariel Odd Fellows Lounge, the building was used for that organizations’ meetings and different events.

Snow remembers looking at old photographs of the building, with an old tailor shop next door and horses and buggies on the street. The Wheeler family started managing the opera house in 1919, and they continued to operate the building for three generations. She talked with Harry Wheeler who recalls the 1937 flooding in Gallipolis. He remembers riding a boat down the hall to get to the theater.

When she was rummaging through the basement she found remains of the original ticket box sitting in water in the basement. She met an elderly man named General George Bush who used to be an usher and could recite the alphabet backwards easily after helping people find their seats in the alphabetized rows. He recalled an old box that used to collect all of the tickets. Snow restored the box, and some volunteers made a frame to hold the fragile pieces together.

It was a very hot and humid spring, and the clock was ticking towards the grand opening. It was Wednesday, and the theater would be opening in three days. Snow planned a stenciling party, and what seemed like the whole town showed up — surgeons, nurses, teachers, librarians.

“I mean everybody was in here,” Snow says. “Some stayed for a few hours, some stayed all night. We finished at 5 a.m. and they started dropping the scaffolding at 7 [a.m.].”

The theater was packed with people wanting to help. The floor needed to be patched, wallpaper in the bathrooms had to be installed, the woodwork needed to be stripped. People were installing the seats until 8 p.m. the night of the grand opening concert. But it all got finished. Residents of Gallipolis lined up outside the opera house with their faces pressed against the glass, trying to get a peak of the finished theater. The Ohio Valley Symphony finally performed in what would be its home for the next 30 years.

Making the music

Since its grand unveiling in 1990, the opera house has expanded its functions, serving as a space for dozens of different events. Music teachers hold lessons for students in small studios, and a room that once served as the lodge on the third floor makes the perfect place for piano recitals and quintet performances. It’s a sensational secular solace.

“That’s what opera houses were meant to be —They were the community gathering places,” Snow says. “The secular community gathering place. The only other place you could gather like that were in churches, so these opera houses provided a function for the community. People could get together without having to worry about which church they were going to. They used them for public debates, city meetings, performances, style shows. Anything that involved people getting together. And that’s what I said at the very beginning. And that’s what we still do.”

While Snow is proud of the opera house and the events it hosts, her pride from the symphony is palpable. She has watched children’s faces light up in her classes when they hear great music for the first time. She compares it to tasting your first piece chocolate. “Would you know how wonderful chocolate was if you’ve never tasted it?” Snow ponders.

Symphonic Devotion

The symphony performs maybe five or six times a year, Wendell Dobbs, the principal flutist, estimates. He has been working with Snow for more than a decade and has performed with many different orchestras, but thinks that performing with The Ohio Valley Symphony has been the most gratifying experience he has ever had.

“It sounds like an orchestra that has the luxury of getting to rehearse all the time, but it’s not,” Dobbs says. “It’s put together with just a few rehearsals and I think the reason that happens is because Lora picks her players so carefully and everyone comes well-prepared and ready to concentrate.”

In past orchestras that Snow has played with, there were many male conductors who thought screaming obscenities would make people play better. She wanted to move away from that and instead encourage her players. Her goal was to create a supportive environment, as the audience can tell when the performers are happy.

“I think when you listen to music, you want to have a real physical response,” Snow says. “You want to laugh, or cry, or get goosebumps, or gasp. Something that tells you that it’s moving you. That’s what I want when I hear something or perform it. And I want my audiences to have that, too. You don’t get that when you don’t make people comfortable. ”

As Snow’s symphony draws successful soloists and many other performers each year, the opera house is jam-packed with activities during the spring and fall months. When the residents of Gallipolis enter the building for one of the many events that take place, many walk through the halls without thinking about how unique the building and its history truly is.

“This is an acoustical gem,” Snow says. “This is like one of the fine old instruments. People revere Stradivarius violins and cellos and maybe guitars. That’s what this is. This is a fine, old instrument, and we need to save it because you can’t build another one like it.”

For more information, visit ovsarieltheatre.org.

SEO

Related posts

What’s Inside

- Behind the Bite (68)

- Features (124)

- In Your Neighborhood (102)

- Photo Essay (4)

- Read the Full Issue (8)

- Talking Points (48)

- The Scene (15)

- Uncategorized (3)

- Web Exclusive (5)

- What's Your Story? (21)

Find us on Social Media