A baseball great’s Portsmouth roots hold true through a lifetime

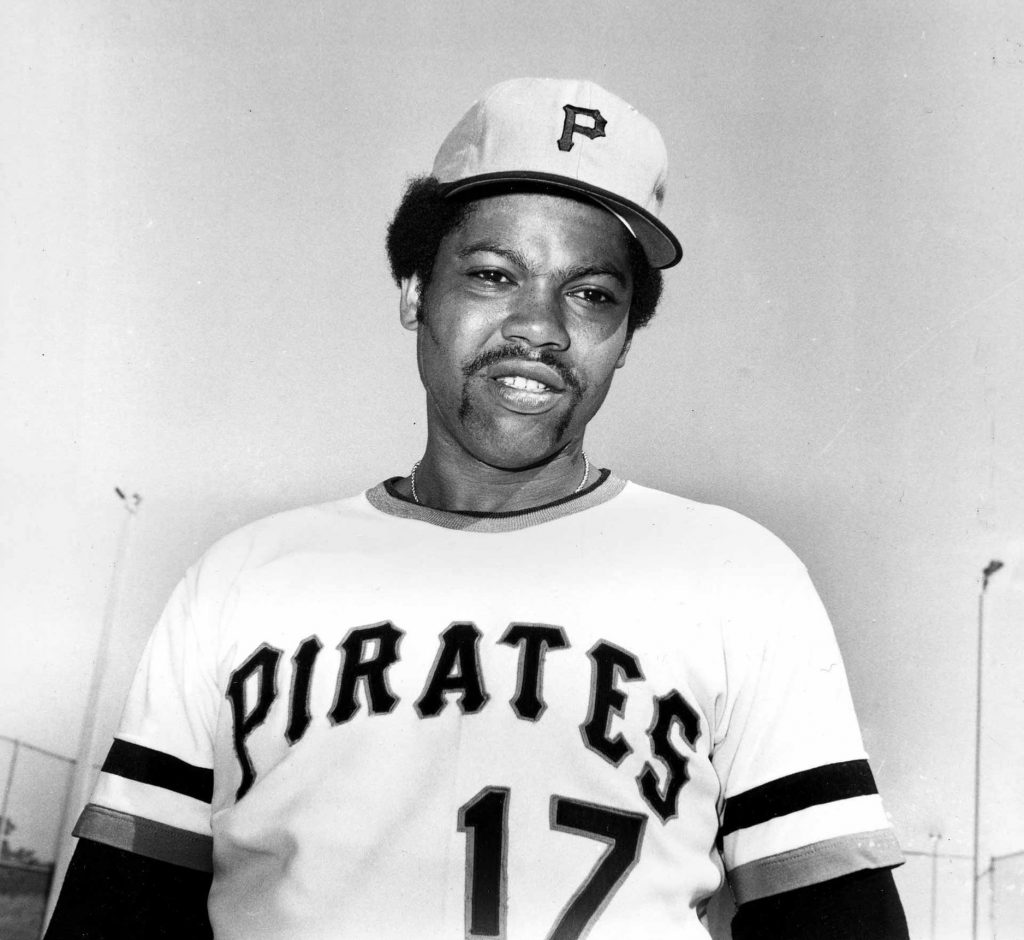

Al Oliver, a highly recognized veteran of the MLB, attributes his success, faith and confidence to a humble town tucked on the edge of the Ohio River.

When you ask the people of Portsmouth about Oliver, his name is often accompanied by words of praise and fondness. To many, the 74-year-old is both a beacon and a staple: a role model for children and a legend for those who knew him before the rest of America did.

A Humble Upbringing, a Prestigious Career

Oliver was born in Portsmouth on Oct. 14, 1946. At that time, the Portsmouth area was almost solely economically dependent on mills and factories. Although this place and time might be insignificant to many historians, to Oliver, the north end of Portsmouth was everything.

Oliver’s parents were deeply rooted in the community, most notably in the church. From his earliest memories, Oliver’s Sundays were spent in pews and with family, and the ball games that otherwise dominated his life took a backseat on that sacred day.

“I was raised in a very spiritual home,” Oliver says. “I think that has been the key to my life.”

His father was a confident man, his mother caring, and the home they created was full of strong ties and discipline. “He was very firm. He was very fair. But I could not have been raised in a better community,” Oliver says. Little Al modeled the assurance his father, Al Oliver Sr. carried, and it became a trait he was infamous for later in life.

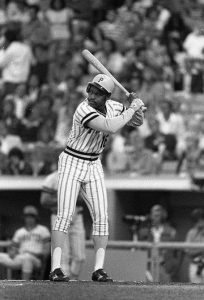

As Oliver’s baseball career progressed –signing as a free agent with the Pittsburg Pirates in 1964 and joining the Major Leagues in 1968– his teammates with whom he shared countless hours of hard-wrought practice with came to recognize him for one thing above all else: work.

Whatever was said about Oliver’s on-field abilities (he both batted and threw left-handed) or his frequent trades between teams the second half of his career, nobody could ever deny the tenacity with which he went into every single baseball game. For Oliver, each game offered new promise.

“I mean, I don’t know what player wouldn’t want to play every day,” Oliver says.

Oliver spent the first 13 years of his career playing for Pittsburgh, and while there, the Pirates won multiple titles, including the World Series in 1971. He was traded to the Texas Rangers in 1977, and from that point forward his presence in a franchise never lasted more than a few seasons, skipping from Montreal to San Francisco and from Philadelphia to Los Angeles, before leaving the game in 1985 after a season with the Toronto Blue Jays.

Over the course of his baseball career, Oliver produced statistics that put him in rarified air. With a lifetime batting average of .303 and 2,743 hits, he took his place in a stratum high above most MLB players. Yet despite Oliver’s athletic accomplishments, he failed to achieve the one thing that many of these elite players acquire: induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

A Lack of Recognition, an Undertone of Prejudice

His induction, or lack thereof, is hotly contested among players, researchers and historians. The reasoning behind Oliver’s lack of support from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America voters is still up for debate. Some assert that his exclusion was merely his lack of the “right” statistics; others blame his attitude. However, with the old school ballot system still largely in play, many involved with the sport believe it had nothing to do with Oliver’s talent and everything to do with the color of his skin.

Oliver himself does not like to believe it was because he is Black. He says his parents taught him to focus on the things in his life he could control, rather than fixate on another’s ill-will. “We all know racism,” Oliver says. “It’s sad to see how so much hatred is in people’s hearts.”

For Oliver’s extended family, this steadfast focus was part of growing up. “My grandfather was a slave, and my dad grew up in Alabama. And my grandfather never talked about it; my dad had never, ever mentioned it. Never. I think he wanted me to go out into the world for myself and find out what it was like. And I did. I found out.”

Oliver says he witnessed KKK rallies on the way to games and endured jeers from angered fans. He remembers feeling hit by a wall of realization when he first saw a “colored” bathroom sign. Yet Oliver’s head and heart remained resolute to play.

Oliver was a man who brimmed with confidence, a man who gave straight answers to reporters when questions were asked. He would describe to people his accomplishments and goals, and he’d speak in a matter-of-fact manner, because to him, it was simply the truth. To players, he was an earnest man with a work ethic to back up every word. To the press, and sometimes to management, he had an “attitude” problem.

“The news media can make you a god or a devil,” Oliver said in a 1985 interview with the Los Angeles Times. “It all depends on their choice.”

Decades later, he recalls with clarity how the media failed to comprehend who he was at his core. “I was very confident,” Oliver says. “I believed in my ability, regardless of what people said or thought. They had never really been around somebody who came to the ballpark every day believing that he could hit anybody.”

Shaun Anderson, a professor at Loyola Marymount University who researches athletes and social change, shares Oliver’s sentiment, theorizing that baseball in particular has an air about itself that is conducive to prejudice.

“The game has been accused of being a very conservative sport,” Anderson says. “It is not a showmanship game like the NBA or the NFL. So you’re talking about a fan base, and a voting base that are mostly older, white, conservative males who are all about the good ole days of sport.”

Oliver laughs, recalling one of his first encounters with the national press, when one simple statement of his was spun into accusations of hubris and entitlement.

“They asked, ‘Is he cocky?,’ ‘Is he arrogant?,’” Oliver says, with a deep chuckle that rises from his chest. “I had never even heard the word ‘cocky’; I had no idea what he was talking about.”

“They thought he was a braggart, but it was confidence,” Dock Ellis said when interviewed for the novel Baseball’s Best Kept Secret. “They just heard a boastful Black dude who was talking shit.”

Rory Costello, a biographer for the Society of American Baseball Research, also believes that Oliver was a misunderstood man. “These are things that on the surface look like the guy has a big head, but it’s really just the way he was raised: to have confidence in himself,” Costello says. “I think that in many ways he is a humble man, a religious man. And that contrasts with the statement that might at first blush look egotistical.”

When Oliver’s potential admittance to the Hall of Fame came to vote in 1991, he failed to receive even 5% of the total. To this, Al would say with a levity in his voice, “I’m not a Hall of Fame player…yet.”

A Bat Put Down, A Calling Picked Up

As Oliver stands at this podium at Beulah Baptist Church, his strong words reaching the ears of neighbors and friends, 36 years have passed since he stood under those major league lights. He now spends his time in service to others, with his faith strong and his belief in mankind inspiring.

To those who have known him in the years since his hands have held a bat, baseball is not what he is most famous for. It is his preaching. Whether it be a member of his community, a grandchild of his own or a stranger lucky enough to find themselves in conversation with him, words of wisdom and humble teachings begin to fill the air.

Oliver says the ministry was a calling for him, and from preaching at Beulah Baptist Church to being the chairman of the Deacon Board, his grace and natural orator abilities extend far beyond these formal titles. Across his community, Oliver prays with humble fervor over those about to take their last breaths, and beautifully eulogizes those who have already taken them.

For the last 30 years, he has also devoted his attention to Kiwanis, an organization designed to develop children through service and love, promoting a future beyond that which they might have previously believed obtainable. With a youthfulness still bound up within his heart, he has a strong connection to kids, working as the chairman of Scioto county’s Children’s Services until just last year.

Now, with his children and grandchildren grown, he looks forward to tomorrow with passion and humility. And while his untamable zeal may take him away from the town of Portsmouth, he will never forget the lessons it taught him, the faith it conjured in his soul or the people who made it his home.

Related posts

What’s Inside

- Behind the Bite (68)

- Features (124)

- In Your Neighborhood (102)

- Photo Essay (4)

- Read the Full Issue (8)

- Talking Points (48)

- The Scene (15)

- Uncategorized (3)

- Web Exclusive (5)

- What's Your Story? (21)

Find us on Social Media