By Katy Snodgrass, Photos provided by Randi Podlaknik

Outside the Ohio Statehouse, a hush falls over the unruly crowd. A buzz of anticipation looms in the cold, rainy October air. Protestors shivering in raincoats and hiding under umbrellas wait for boisterous speeches to commence.

The crowd listens patiently to a slew of speakers, a litany of high-level officials for sustainability and environmental groups, professors, attorneys and passionate volunteers. All of the speakers share a common goal: to save Ohio’s state parks.

On September 18, Ohio’s Oil & Gas Land Management Commission met to decide whether or not to lease state-owned land to an anonymous oil and gas company for fracking. The request, or nomination, reportedly leaves 2,000 acres of land under Wolf Run State Park subject to drilling, among several other nominations for more state parks and wildlife areas.

Hydraulic fracturing is a practice that drills deep into the earth using small explosions and a mix of water, sand and chemicals to extract natural gas or oil from shale and other forms of “tight” rock.

Dr. Randi Pokladnik, a committee member and fracking expert for Save Ohio Parks, says it’s only a matter of time before fracking affects drinking water sources, air emissions and noise and light pollution.

Pokladnik says fracking in state parks could become a serious health hazard to communities. Radium from the water solution used to extract the oil and gas from miles under the ground could seep into groundwater that many communities get well water from.

The compressors used in the fracking process could leak harmful methane gas into the atmosphere at highly pressurized rates, says Pokladnik. An increase in road traffic and noise and light pollution has also occurred from the dozens of trucks passing through each day, quickly wearing down local infrastructure and interrupting locals’ sleep cycles.

Official Statistics

Ohio produced almost 20 million barrels of oil in 2022, according to the Ohio Geological Survey’s 2022 Report on Ohio Mineral Industries. Combined, those barrels were valued at over $1.7 billion. Oil produced in Ohio increased in value by 48.2 percent between 2021 and 2022.

Pokladnik is frustrated with state representatives for allowing fossil fuel companies to wreak havoc on the region in exchange for the promise of making money.

“It’s sad. We are losing our resources, and they could sit for decades until we might really need them, but there is a rush to get these things out no matter what,” says Polkdanik.

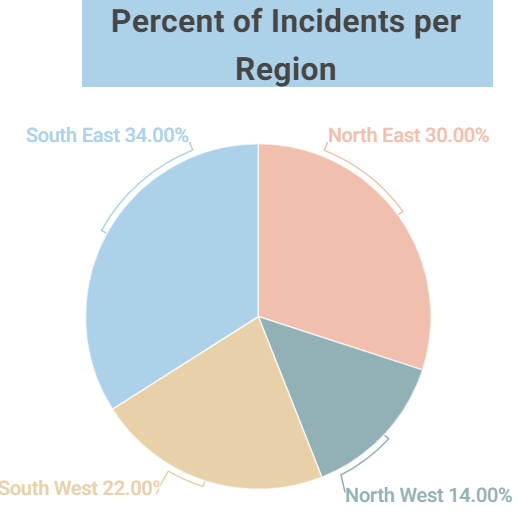

Incident documentation from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources reveal that Pokladnik’s concerns are well founded. 1,530 separate incidents have occured at fracking sites in Ohio since 2018.

34 percent of those incidents have occured in Southeast Ohio, making it the region of the state most prone to fracking accidents.

The ODNR reports that 51 percent of all fracking incidents in Ohio result in some kind of a leak, a majority of which release natural gas or crude oil onto land or into the atmosphere surrounding a drilling site.

Major accidents continue to pop up across the state. In October, Guernesey County residents within a half a mile radius of an oil pad site were evacuated after a gas leak emitted harmful chemicals near their houses. In July 450 people were evecauted from Columbiana County, following a similar well pad gas leak.

How Can They Do This?

Ohio law allows the company that applied for the fracking permit in Wolf Run State Park to remain anonymous.

Section 155.33 of the Ohio revised code allows the state to rent out parts of land it owns or controls for oil and natural gas exploration—only as long as the majority of information is guarded from the public for 45 days, or until the OGLMC announces their finalists from a pool of bids within 120 days of the nomination.

Information shielded from the public includes the name, address and contact information of the person or company making the bid. Information about the land and details about the deal between the state and the renter are also kept secret, including the price of the land.

This secrecy was upheld by the OGLMC during their September meeting. Before discussion on the identity of the company could begin, the Commission voted to have the conversation in an executive meeting and promptly left the meeting room.

While awaiting their return, members of SOP stood up and made their opposition to fracking in state parks known by singing and chanting to the audience, accompanied with signs, costumes and props.

Scandalous Letters

After it was discovered that letters were sent to the OGLMC in Ohioans’ names without their consent or knowledge, hundreds of Ohio residents are also becoming involved in the issue.

On September 10, Cleveland.com revealed that the names, emails, phone numbers and addresses of over 150 people were used without their consent to send pro-fracking letters to the OGLMC.

“I was first alerted to this breach of privacy via a post on Reddit,” wrote Dr. Aviva Neff, a Columbus resident whose information was used without her consent. “I received an automated notification from the OGLMC thanking me for my message, and looked into the matter further. I was not aware of this letter when it was sent.”

During the September meeting, chair of the OGLMC, Ryan Richardson, explained the public had notified the commission of the letters in July. Richardson said the commission then reported the allegations to the Attorney General’s office, which is investigating the breach of privacy.

“The attorney general takes these allegations seriously and has assigned investigative staff to look into the matter further,” wrote Hannah Hudley, the attorney general’s Public Information Officer.

Southeast Ohio magazine’s request for more information on the case was denied.

The Ohio Environmental Council and SOP say through their own investigation, they have traced over 1,000 of the emails back to the Consumer Energy Alliance, a Texas-based nonprofit. CEA is accused of falsely sending emails in citizens’ names in Wisconsin in 2014, Ohio in 2016 and in South Carolina in 2018.

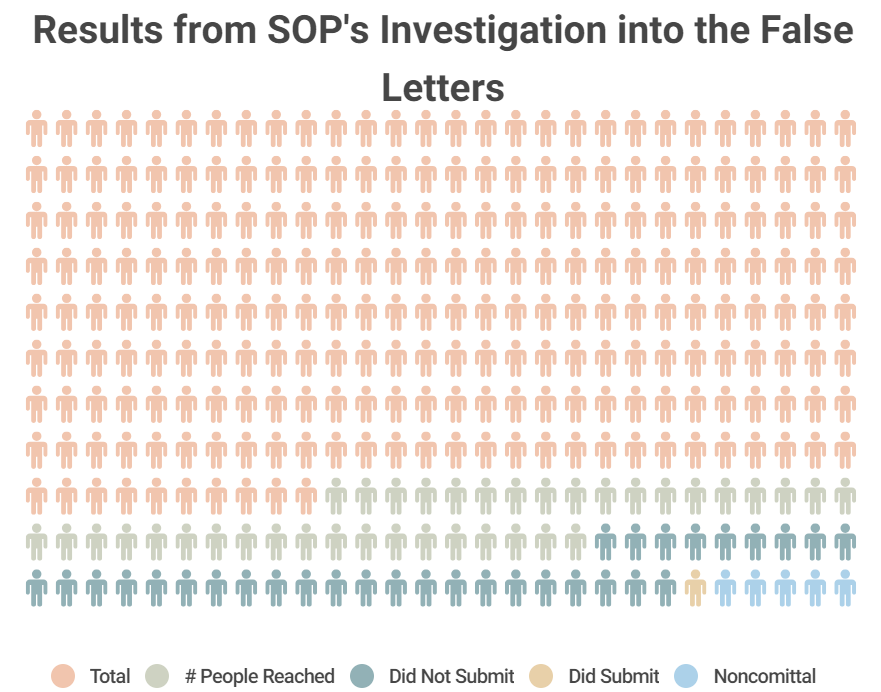

In a September press release, SOP member Cathy Cowan Baker said, “The information for Ohioans whose names were on those letters included phone numbers, so a dozen SOP volunteers called 735 of those numbers. We reached 115 people, and of those 98 told our volunteers they did not submit the letter. Two said they did, and the rest were noncommittal.”

When asked to comment, CEA Vice President of Media and Strategic Communications, Bryson Hull wrote, “Please see CEA’s statement and letter to the Attorney General characterizing the original coverage [cleveland.com] as potentially libelous. CEA will have no further statement other than to say we are actively cooperating with the investigation.”

Despite these revelations causing public disapproval of the project, OGLMC commissioners were unable to reach a firm decision on whether or not to approve fracking in Wolf Run during their September meeting. At that meeting, the OGLMC approved four separate nominations to lease out land owned by the Ohio Department of Transportation across Belmont, Carroll, Columbiana and Harrison counties.

After reconvening on November 15, the OGLMC approved seven of the ten nominations for fracking in state-owned areas, including Salt Fork State Park, Valley Run Wildlife Area and Zepernick Wildlife Area. But the nomination for Wolf Run State Park was rejected— in part because surrounding land is used by Ohio State University’s Eastern Agricultural Research Station.

Fracking in state parks is now iminent. Activists know the people who live near parks, who need to sleep, work and drink clean water, will be the ones left to deal with the bubbling poisons for decades to come.