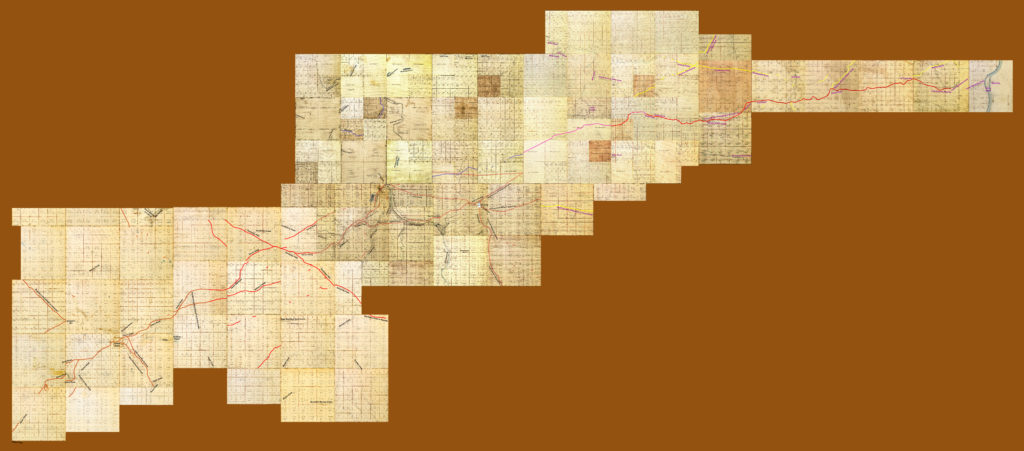

A map estimating the original route of by Zane Trace (Photo provided by: Guernsey County Historical Society).

Photos by: Jordan Ellis // Video by: Jordan Ellis

Monuments, taverns and gravestones. The echoes of the past are entombed in granite. They dot the valleys of Southeast Ohio like the grave markings of an aggrandized serpent. These relics denote what’s left of Zane Trace, the earliest road into Ohio.

Like a great artery, Zane Trace pumped settlements into the Ohio Country following the American Revolution. The federal government sought to expand into the region and make good on promised “bounty lands” given to veterans in return for service. Zane Trace turned America’s first borderland into the heart of the Midwest.

Zane Trace is Ohio’s lost highway. Petitioned to the U.S. Congress by Ebenezer Zane in May 1796 and finished in the summer of 1797, the road was created by connecting already existing Native American footpaths and bison trails. Its primary purpose was to open the Ohio Country up to settlement and mail delivery. Constructed in what was the western frontier, few records depicting the original route remain. As such, documenting the 225-year-old road has its complications.

Lisa Uhrig, an archivist for Ross County Historical Society, became interested in Zane Trace after a local resident donated photos of their familial home. The donor said Zane Trace ran behind the house. This sparked Uhrig’s curiosity. She had grown up in the area and known about the Zane Trace for some time. Now confronted with it as an historical archivist, she decided to map it out.

Uhrig found documentation of the road in Ross County east of the Scioto River. Documentation west of the river, however, was not well-maintained. This section was part of the Virginia Military District, which was created to divide the area up into bounty lands. Historical maps for the area exist, but they never labeled a specific road as Zane Trace.”

Zane Trace grew like the tunnels of an ant colony. Locals would manipulate it for their needs; they brought it closer to their homes for easier access or widened and graveled more traveled sections. In turn, these widened and channeled paths became roads in their own right.

“All these early roads, I think, were very interchangeable with Zane Trace,” Uhrig says. “The State Road, the Post Road, the Limestone Road.”

Where documentation fails, historians must investigate. William Hunter, a regional historian for the National Park Service, wrote his master’s thesis on Zane Trace in 1998. During a 17-day-walkabout, William walked the breadth of the trail. He used old taverns, gravestones and the advice of locals to guide himself. Most residents received the stranger walking around their homes with kindness—other than a well-aimed beer bottle tossed at his head in Cambridge.

William believes Zane Trace was created from the culmination of human tendencies. If an individual were to walk Ohio Country today without modern infrastructure, they would recreate the same road. The geography would speak to them, and they would move along the natural path.

“The landscape is the clue to culture,” Hunter says. “If you can look at landscapes … if you’re really keen and really wise and approach the landscape on its terms, it will open itself up to you.”

The Enduring Legacy of Ebenezer Zane

Peter Cultice, the president of Muskingum County History, rolls a copy of 640-acre deed for Zanesville out on the coffee shop table in Starbucks. He walks with a limp, recovering from a recent hip-replacement surgery. Despite the discomfort, he is transfixed when speaking of his town’s history.

“Probably as a thank you, maybe as a payment, Ebenezer Zane and his wife for $100 deeded these 640 acres to John McIntire and to Jonathan Zane for probably helping out on the trace,” Cultice says jabbing the document with his index finger.

The most enduring legacy of Zane Trace are the towns of Zanesville and Lancaster. In return for creating the trail, Ebenezer was given his choice of “bounty lands” to claim by Congress. He cherry-picked lands that made excellent river crossings for ferries and later communities.

The Zane Trace Commemoration, formerly a large celebration in Zanesville, is being revived for June 2023. The John McIntire Education Fund, named after Ebenezer’s son-in-law and a founder of Zanesville, entrusts scholarships to graduating seniors in Muskingum County every year.

Muskingum County History hosted a series of symposiums in 2022 to celebrate the 225th anniversary of Zane Trace. The symposiums gathered speakers across Southeast Ohio, Indiana and Virginia. “People want to find it,” Cultice says. “They want to preserve it. They want to bring it back to life.”

Many Americans often view their local community as unceded from time. There might be an old schoolhouse or church here or there, but those monuments only echo the near past. Zane Trace is born of the paths tread by Native Americans and bison hundreds of years ago. It moves through pastures and croplands as easy as a gentle breeze following the natural contours. It takes the right state of mind to see the shadow of this ancient past.

Walking the Trace

“Hey, are you okay?”

I turn around. A 30-something man with a long brown beard stares at me inquisitively from his pickup truck. He looks like he’s confronting a frightened deer. We ponder each other as the hazard lights on my car click further down the road.

“What?” I ask, putting some confrontation in my voice.

“Are you okay?” the man repeats. I notice concern drawn in the lines across his forehead.

“Yeah, I’m fine,” I reply slackening my voice. I turn around and glance at Rushville Creek flowing underneath the bridge below me. “I’m just taking pictures.”

I show the man the camera hanging on my neck. He nods and drives off. I go back to taking pictures. I lean over the barrier at the edge of the bridge and snap some photos of the rocky waters below. It finally occurs to me that a person leaning over the edge of a tall bridge might resemble someone attempting to escape the mortal coil. The man’s concern makes me chuckle a bit.

The encounter on the bridge wasn’t the first odd interaction I had that day. I had been driving around northern Perry County near Somerset guiding myself with maps provided by the Guernsey County Historical Society. I took pictures of old properties and historical sites. These locations of interest were often near, or on, personal property dotted with “No Trespassing” and “National Rifle Association “signs.

To someone not from a rural area these placards can be misinterpreted as omens of violent reciprocation. They simply request a congenial nod or conversation. Still, the beer can that smacked the head of William Hunter back in the 90s had been on my mind.

Finding Zane Trace is a lesson in historical research and humility, but also brings with it the joy of discovery. Finding the remnants of corn cribs and gargantuan circular horse barns makes me reminisce of some pastoral age I never lived in. It’s not the most obvious form of entertainment, but it is meaningful.